Filling in the blanks for Bill Keller

Palin’s smarter than people think, says — Ralph Nader

Fast & Furious: FBI may have covered up third gun found at scene of agent’s death to protect informant

Obama: I’ll veto any bill that isn’t “balanced” with tax hikes

Question for Palestinian president: Why embarrass Obama by forcing this statehood bid at the UN?

Gallup: Perry 31, Romney 24, Paul 13, Bachmann … 5

Quotes of the day

Gallup: Perry 31, Romney 24, Paul 13, Bachmann … 5

GBP Falls for Fourth Week, Quantitative Easing Expected

Canadian Securities Drive Canadian Dollar to Two-Week Record

NZD Gains as RBNZ Shows Optimism for New Zealand Economy

Aussie Rises on Asian Stocks, Heads to Weekly Loss

Rand Falls as Investors Shun South African Bonds

Mixed Fundamentals Leave Traders Uncertain, USD Fluctuates

SNB Maintains Rates at Zero, Franc Strengthens

Europe Helps Oil & Russian Ruble

Rand Rebounds on ECB Efforts

Canadian Dollar Within Cent of Parity with Greenback

Interest Rates Outlook Causes Weekly Slump of Dollar, Forex

The US dollar was performing terribly this week against both commodity and safe currencies among signs of economic growth and on speculation that the Federal Reserve will lag with an increase of the interest rates.

The strength of commodity currencies against the dollar has the same explanation as before: the global recovery. The US economy itself provided very the confusing signs: while its weak housing market turned out to be better than it was considered, the growth of manufacturing, the one of the strongest US sectors, slowed significantly and unexpectedly. As for performance versus other currencies, analysts remind us about the same old story: the quantitative easing. The US policy makers started talking about an end to the accommodative stance, but talks aren’t enough when other banks, most notably the European Central Bank and Sweden’s Riksbank, already began raising their borrowing costs.

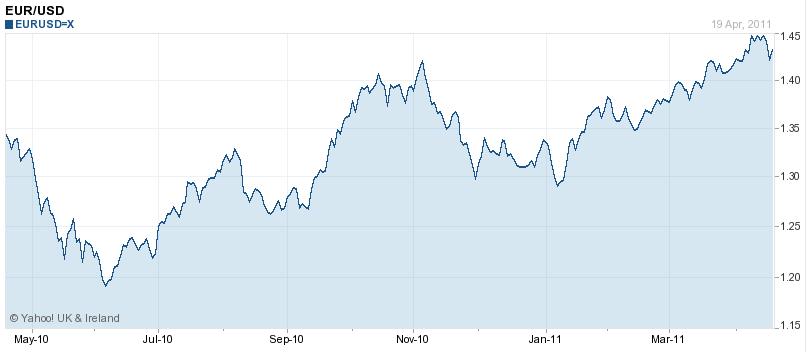

EUR/USD has broken its resistance and jumped from 1.4411 to 1.4647, the highest level since December 2009, over the week, closing at 1.4559. USD/JPY fell from 83.21 to 81.85. USD/SEK closed at 6.1034 after opening at 6.1930 and reaching 6.0717, the lowest level since August 2008.

If you have any questions, comments or opinions regarding the US Dollar, feel free to post them using the commentary form below.

She is Thai sexy actress and popular model, Woranuch Wongsawan. Her nickname is Noon. Noon is one of the famous actress and model in Thailand. She was born in 1980 and studied at College of Nathasin.

She is Thai sexy actress and popular model, Woranuch Wongsawan. Her nickname is Noon. Noon is one of the famous actress and model in Thailand. She was born in 1980 and studied at College of Nathasin.

Thai sexy actress, Thai popular actress. Thai pretty girl, Asian pretty model, Asian sexy girl.

Thai sexy actress, Thai popular actress. Thai pretty girl, Asian pretty model, Asian sexy girl. Pictures

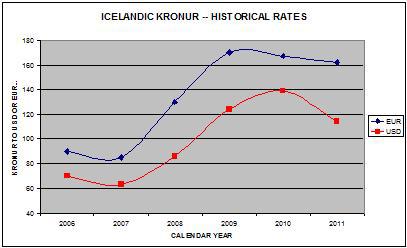

Icelandic Kronur: Lessons from a Failed Carry Trade

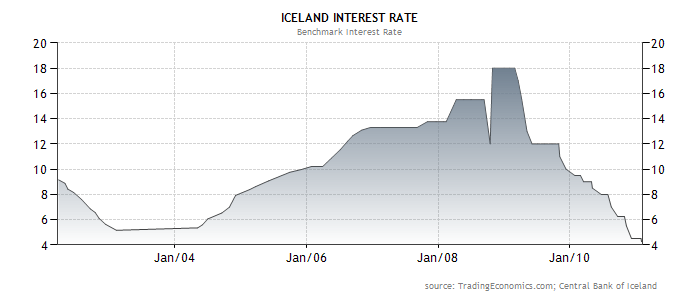

A little more than two years ago, the Icelandic Kronur was one of the hottest currencies in the world. Thanks to a benchmark interest rate of 18%, the Kronur had particular appeal for carry traders, who worried not about the inherent risks of such a strategy. Shortly thereafter, the Kronur (as well as Iceland’s economy and banking sector) came crashing down, and many traders were wiped out. Now that a couple of years have passed, it’s probably worth reflecting on this turn of events.

At its peak, nominal GDP was a relatively modest $20 Billion, sandwiched between Nepal and Turkmenistan in the global GDP rankings. Its population is only 300,000, its current account has been mired in persistent deficit, and its Central Bank boasts a mere $8 Billion in foreign exchange reserves. That being the case, why did investors flock to Iceland and not Turkmenistan?

The short answer to that question is interest rates. As I said, Iceland’s benchmark interest rate exceeded 18% at its peak. There are plenty of countries that offered similarly high interest rates, but Iceland was somehow perceived as being more stable. While it didn’t join the European Union until last year, Iceland has always benefited from its association with Europe in general, and Scandinavia in particular. Thanks to per capita GDP of $38,000 per person, its reputation as a stable, advanced economy was not unwarranted.

On the other hand, Iceland has always struggled with high inflation, which means its interest rates were never very high in real terms. In addition, the deregulation of its financial sector opened the door for its banks to take huge risks with deposits. Basically, depositors – many from outside the country – parked their savings in Icelandic banks, which turned around and invested the money in high-yield / high-risk ventures. When the credit crisis struck, its banks were quickly wiped out, and the government chose not to follow in the footsteps of other governments and bail them out.

Moreover, it doesn’t look like Iceland will regain its luster any time soon. Its economy has shrunk by 40% over the last two years, and one prominent economist has estimated that it will take 7-10 years for it to fully recover. Unemployment and inflation remain high even though interest rates have been cut to 4.25% – a record low. The Kronur has lost 50% of its value against the Dollar and the Euro, the stock market has been decimated, and the recent decision to not remunerate Dutch and British insurance companies that lost money in Iceland’s crash will only serve to further spook foreign investors. In short, while the Kronur will probably recover some of its value over the next few years (aided by the possibility of joining the Euro), it probably won’t find itself on the radar screens of carry traders anytime soon.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.Forex Markets Focus on Central Banks

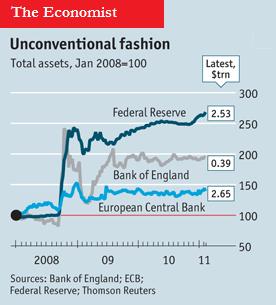

Over the last year and increasingly over the last few months, Central Banks around the world have taken center stage in currency markets. First, came the ignition of the currency war and the consequent volley of forex interventions. Then came the prospect of monetary tightening and the unwinding of quantitative easing measures. As if that wasn’t enough to keep them busy, Central Banks have been forced to assume more prominent roles in regulating financial markets and drafting economic policy. With so much to do, perhaps it’s no wonder that Jean-Claude Trichet, head of the ECB, will leave his post at the end of this year!

The currency wars may have subsided, but they haven’t ended. On both a paired and trade-weighted basis, the Dollar is declining rapidly. As a result, emerging market Central Banks are still doing everything they can to protect their respective currencies from rapid appreciation. As I’ve written in earlier posts, most Latin American and Asian Central Banks have already announced targeted strategies, and many intervene in forex markets on a daily basis. If the Japanese Yen continues to appreciate, you can bet the Bank of Japan (perhaps aided by the G7) will quickly jump back in.

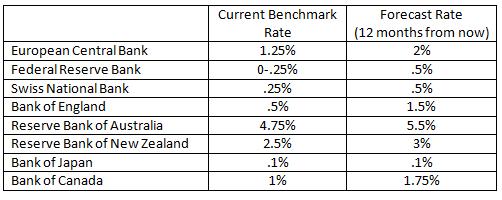

Then there are the prospective rate hikes, cascading across the world. Last week, the European Central Bank became the first in the G4 to hike rates (though market rates have hardly budged). The Reserve Bank of Australia, however, was the first of the majors to hike rates. Since October 2009, it has raised its benchmark by 175 basis points; its 4.75% cash rate is easily the highest in the industrialized world. The Bank of Canada started hiking in June 2010, but has kept its benchmark on hold at 1% since September. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand lowered its benchmark to a record low 2.5% as a result of serious earthquakes and economic weakness.

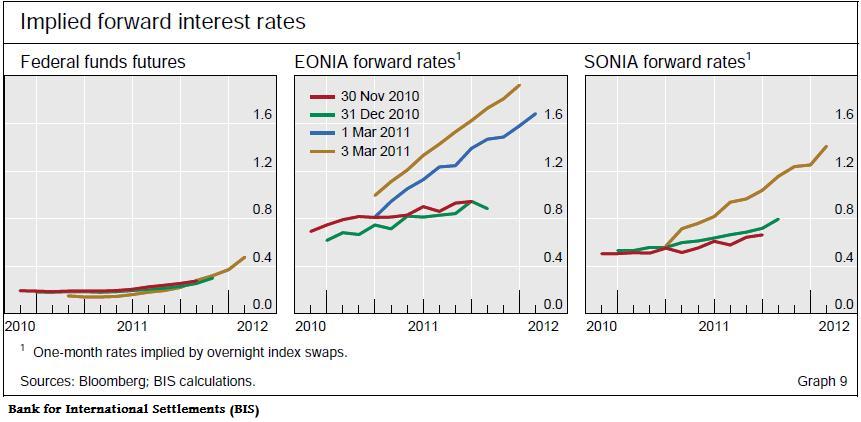

Going forward, expectations are for all Central Banks to continue (or begin) hiking rates at a gradual pace over the next couple years. If forecasts prove to be accurate, the US Federal Funds Rate will stand around .5% at the beginning of 2012, tied with Switzerland, and ahead of only Japan. The UK Rate will stand slightly above 1%, while the Eurozone and Canadian benchmarks will be closer to 2%. The RBA cash rate should exceed 5%. Rates in emerging markets will probably be even higher, as all four BRIC countries (Russia, Brazil, China, India) should be well into the tightening cycles.

On the one hand, there is reason to believe that the pace of rate hikes will be slower than expected. Economic growth remains tepid across the industrialized world, and Central Banks are wary about spooking their economies with premature rate hikes. Besides, Fed watchers may have learned a lesson as a result of a brief bout of over-excitement in 2010 that ultimately led to nothing. The Economist has reported that, “Markets habitually assign too much weight to the hawks, however. The real power at the Fed rests with its leaders…At present they are sanguine about inflation and worried about unemployment, which means a rate rise this year is unlikely.” Even the ECB disappointed traders by (deliberately) adopting a soft stance in the press release that accompanied its recent rate hike.

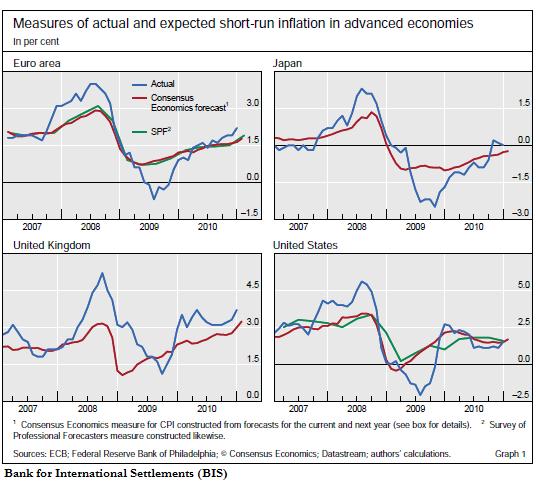

On the other hand, a recent paper published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) showed that the markets’ track record of forecasting inflation is weak. As you can see from the chart below, they tend to reflect the general trend in inflation, but underestimate when the direction changes suddenly. (This is perhaps similar to the “fat-tail” problem, whereby extreme aberrations in asset price returns are poorly accounted for in financial models). If you apply this to the current economic environment, it suggests that inflation will probably be much higher-than-expected, and Central Banks will be forced to compensate by hiking rates a faster pace.

Finally, in their newfound roles as economic policymakers, Central Banks are increasingly engaged in macroprudential policy. The Economist reports that, “Central banks and regulators in emerging economies have already imposed a host of measures to cool property prices and capital inflows.” These measures are worth watching because their chief aim is to indirectly reduce inflation. If they are successful, it will limit the need for interest rate hikes and reduce upward pressure on their currencies.

Finally, in their newfound roles as economic policymakers, Central Banks are increasingly engaged in macroprudential policy. The Economist reports that, “Central banks and regulators in emerging economies have already imposed a host of measures to cool property prices and capital inflows.” These measures are worth watching because their chief aim is to indirectly reduce inflation. If they are successful, it will limit the need for interest rate hikes and reduce upward pressure on their currencies.In short, given the enhanced ability of Central Banks to dictate exchange rates, traders with long-term outlooks may need to adjust their strategies accordingly. That means not only knowing who is expected to raise interest rates – as well as when and by how much – but also monitoring the use of their other tools, such as balance sheet expansion, efforts to cool asset price bubbles, and deliberate manipulation of exchange rates.

Time to Short the Euro

Over the last three months, the Euro has appreciated 10% against the Dollar and by smaller margins against a handful of other currencies. Over the last twelve months, that figure is closer to 20%. That’s in spite of anemic Eurozone GDP growth, serious fiscal issues, the increasing likelihood of one or more sovereign debt defaults, and a current account deficit to boot. In short, I think it might be time to short the Euro.

There’s very little mystery as to why the Euro is appreciating. In two words: interest rates. Last week, the European Central Bank (ECB) became the first G4 Central Bank to hike its benchmark interest rate. Moreover, it’s expected to raise rates by an additional 100 basis points over the next twelve months. Given that the Bank of England, Bank of Japan, and US Federal Reserve Bank have yet to unwind their respective quantitative easing programs, it’s no wonder that futures markets have priced in a healthy interest rate advantage into the Euro well into 2012.

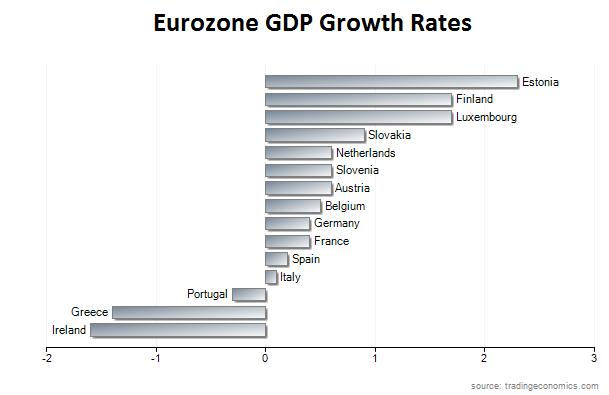

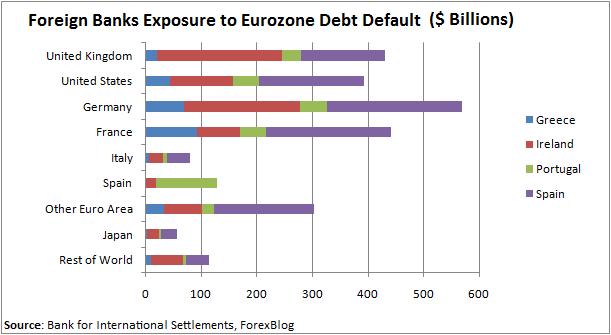

From where I’m sitting, the ECB rate hike was fundamentally illogical, and perhaps even counterproductive. Granted, the ECB was created to ensure price stability, and its mandate is less nuanced than its counterparts, which are charged also with facilitating employment and GDP growth. Even from this perspective, however, it looks like the ECB jumped the gun. Inflation in the EU is a moderate 2.7%, which is among the lowest in the world. Other Central Banks have taken note of rising inflation, but only the ECB feels compelled enough to preemptively address it. In addition, GDP growth is a paltry .3% across the EU, and is in fact negative in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. As if the rate hike wasn’t bad enough, all three countries must contend with a hike in their already stratospheric borrowing costs, ironically making default more likely. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees!